Transmission of Microorganisms on Skin and Fomites

Written by Corinne

Introduction

Microorganisms can be transmitted from infected to healthy persons in a variety of ways. Two ways emphasized in this lab report are transmission via skin to skin contact, and transmission via fomites. Fomites are objects or substances which are not living but capable of transmitting microorganisms between people. Fomites become especially dangerous in hospitals or other healthcare facilities, as they can transmit nosocomial infections. Nosocomial infections are acquired by patients while in a hospital setting, and can infect both the patients and the uphealthcare staff. Based on CDC estimates, 10% of all patients in the hospital will acquire some kind of nosocomial infection (Willey, 2008). The sources of a nosocomial infection can be either exogenous or endogenous (Claus, 2007). Exogenous infections are caused by microorganisms from the hospital environment that invades the patient during their stay in the healthcare facility. Endogenous infections are caused by microorganisms already inhabiting the person that gain strength and multiply while the patient is in a weakened, hospitalized state which they are often immunocompromised. These infections are of high interest to the CDC and much effort is put towards the prevention of the spread of nosocomial infections.

A pathogen of interest for this study is Serratia marcescens. It is a gram negative bacillus which is classified in the Enterobacteriaccae family of microorganisms (Hejazi, 1997). It has been identified as one of the chief causes of nosocomial infections acquired by patients during their stay in the hospital. One of the more interesting things about S. marcescens, is that it is present in nearly every kind of exogenous nosocomial infection, such as URI’s and UTI’s. It’s chief victims are heroin addicts and hospitalized patients, meaning that it is an opportunistic pathogen that strikes when the immune system is at its weakest.

Research done by organizations like the CDC has been conducted in an attempt to contain and prevent the spread of nosocomial infections. It is a serious matter because nosocomial infections can prolong the stay of an already ill person in the hospital by over two weeks in some cases (Willey, 2008). It is through these efforts that some basic guidelines have been established. To begin with, health care workers should be well versed in basic sanitation methods and beyond as required in the sterile hospital setting. In the hospital, aseptic technique and hand washing are paramount to prevent the spread of nosocomial infections. The experiments utilized in this lab report quantify just how effective hand washing can be towards preventing the spread of microorganisms when it is performed correctly.

Procedure

This experiment divided up the classroom into two groups of 12. Group B tested the fomite form of microbial transmission. The methodology for this experiment began with the TA placing a source of Serratia marcescens on the doorknob. Each person of group A touched the knob with a sterilized glove. Two nutrient agar plates were provided for each person, and immediately after touching the knob, the student was instructed to rub their sterile glove onto the surface of the first agar plate. It is important that the only things touched by the student were the doorknob and then the agar plate. After touching the agar plate, the student washed their gloved hand with soap without contamination from the other hand. They then dried the gloved hand with a paper towel and rubbed the glove on the second plate in a manner similar to the method used before washing.

The other group, known as group A, tested the human skin microbial transmission method. This part of the experiment was similar in methods to group B, except instead of touching the doorknob successively, person 1 was infected with Serratia marcescens being placed on their glove, and then they shook gloved hands with person 2. This continued all the way until person 12. After shaking hands, the gloved hand was rubbed onto nutrient agar plate 1, similar to group A, then it was washed, dried, and rubbed onto nutrient agar plate 2. The gloves were disposed of in the autoclave bag, and new gloves were applied after the experiment. The agar plates were then inverted, labeled, and placed in a bin for growth for 24-48 hours and subsequent analysis the following laboratory period.

Results

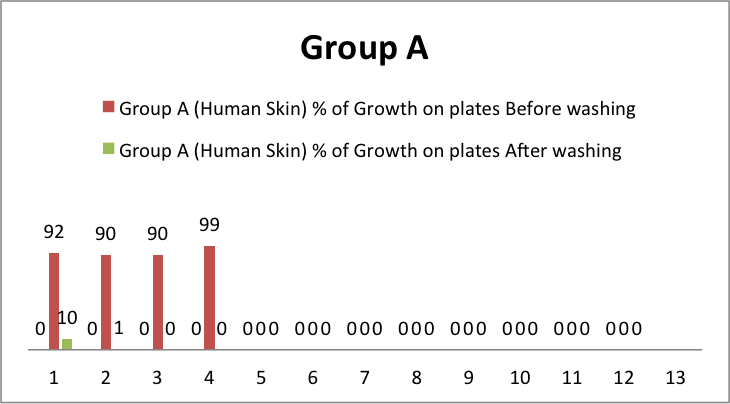

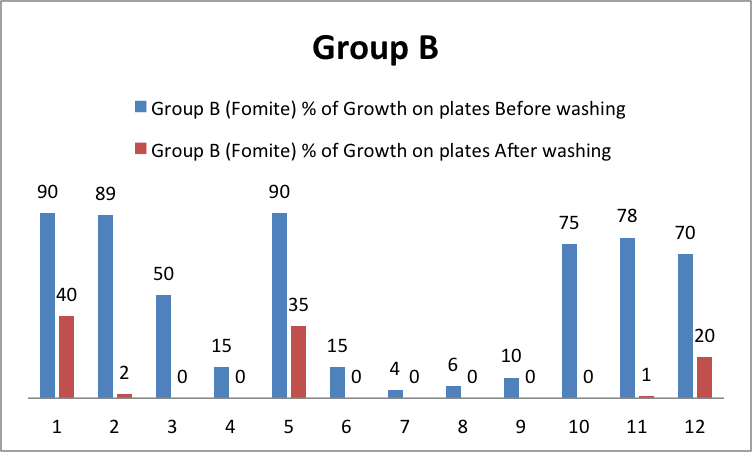

In table 1, and graph 1, it is apparent that the handshake method began with a 92% growth with person 1, but by the time person 5 shook the hand of person 6, the microorganisms were not transferred enough to grow in the nutrient agar. It also appears that everyone after person 2 in the human skin test eliminated all microorganisms before touching the second plate. Looking at Graph 2, Group B showed consistent growth in the first agar plate after touching the fomite, and had a range of growth after hand washing from 0-40% with person 1 having the most growth. Looking at table 2, The t test for group A showed a p value of .01, while the t test in table 3 for group B showed a value of 0.0003.

Discussion

When looking at the results after the plates were incubated, it is clear that one form of transmission is more effective than the other. In fomite transmission, all people who touched the doorknob had growth on their first nutrient agar plate. In the human skin transmission experiment, only students up to number 4 had growth before washing, while all other students had zero growth before or after hand washing. From these results it appears that fomites are a more infectious method of microbial transmission.

It is also interesting to note the trend of microbial growth after hand washing. In some cases, the growth was reduced to 0%, while in other occurrences, there was as much as 40% growth on the agar plate. This leads to a couple hypotheses. Either the handwashing technique of the individual that produced growth on plate #2 was not adequate enough to eliminate all traces of S. marcescens, or there was a multitude of the microorganism on the glove that could not be removed via brief glove washing. Since the vast majority of the class in both cases managed to remove all microorganisms from their glove via hand washing, it is a likely assumption that the hand washing technique of the individual is to blame for the inconsistencies.

Looking at the t-test performed, both groups had a p value of <0.05, which means that the data reported in this section was statistically significant and there is a low possibility that the trends occurred by chance. This leads us to support our previous hypothesis that fomite transmission is more pathogenic, and that the microorganisms can be mostly eliminated from the glove using proper hand washing technique.

There are several errors that could occur in this experiment, which could skew the data. As mentioned previously, it was important that each individual member be accountable for their glove washing methods. The data shows that at least two individuals may not have properly washed their gloves and therefore we saw growth on the second nutrient agar plate which may have caused the data on the virulence of the microorganism to be misleading. Another error is in the transmission technique. There was not a guideline established for handshakes or doorknob grabbing, and each person has an individual method for tactile encounters using the hand. This may lead to a differing amount of contact between gloves or glove and doorknob and would also account for the different trends seen in the colony growth of the first agar plate in both groups. One major area of error would be subjective error in the analysis. The data was not polled together, and each student observed colony growth and assigned it to a subjective percentage. This will mean that each students results will be slightly different, as what looks like 50% to one student might be 40% to another. Overall despite the minor inconsistencies, this lab taught valuable lessons about pathogen transmission via human skin and fomites as well as the paramount importance of washing your hands!

Literature Cited

Claus, W. G. (2007). Understanding Microbes: A Laboratory Teaching Manual. New York, NY: Freeman Custom Publishing.

Hejazi, A., Falkiner, F. (1997) Serratia marcescens. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 46.

Willey, J., Sherwood, L., & Woolverton, C. (2008). Prescott’s Microbiology. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Tables and Figures

|

Student |

Group A (Human Skin) |

Group B (Fomite) |

||

|

% of Growth on plates |

% of Growth on plates |

|||

|

Before washing |

After washing |

Before washing |

After washing |

|

|

#1 |

92 |

10 |

90 |

40 |

|

#2 |

90 |

1 |

89 |

2 |

|

#3 |

90 |

0 |

50 |

0 |

|

#4 |

99 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

|

#5 |

0 |

0 |

90 |

35 |

|

#6 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

|

#7 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

#8 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

|

#9 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

|

#10 |

0 |

0 |

75 |

0 |

|

#11 |

0 |

0 |

78 |

1 |

|

#12 |

0 |

0 |

70 |

20 |

Table 1

Chart 1

Chart 2

| t-Test: Paired Two Sample for Means | |||

|

Group A |

Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

|

| Mean |

30.91667 |

0.916667 |

|

| Variance |

2090.447 |

8.265152 |

|

| Observations |

12 |

12 |

|

| Pearson Correlation |

0.463322 |

||

| Hypothesized Mean Difference |

0 |

||

| df |

11 |

||

| t Stat |

2.337322 |

||

| P(T<=t) one-tail |

0.019679 |

||

| t Critical one-tail |

1.795885 |

||

| P(T<=t) two-tail |

0.039358 |

||

| t Critical two-tail |

2.200985 |

||

Table 4

| t-Test: Paired Two Sample for Means | ||

|

Group B |

Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

| Mean |

49.33333 |

8.166667 |

| Variance |

1329.697 |

220.8788 |

| Observations |

12 |

12 |

| Pearson Correlation |

0.599079 |

|

| Hypothesized Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| df |

11 |

|

| t Stat |

4.75024 |

|

| P(T<=t) one-tail |

0.0003 |

|

| t Critical one-tail |

1.795885 |

|

| P(T<=t) two-tail |

0.000599 |

|

| t Critical two-tail |

2.200985 |

|

Table 3