AN ANALYSIS OF EXISTING LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR GRAYWATER USE AND THE NEXT STEPS AFTER COLORADO HOUSE BILL 13-1044

Forward

The following is a report fulfilling an Independent Study, CVEN 4849-929 (1), taken place under the supervision of and approved by Professor JoAnn Silverstein and the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering. The study focuses on analyzing existing legal framework for graywater recycling, proposing suggestions to Colorado House Bill 13-1044, and the next steps in instituting graywater in the state of Colorado.

Abstract

Graywater recycling is a known, generally accepted, practice that is on the cusp of becoming a widely used mean of water consumption reduction. However, within the United States there are only several states that recognize graywater practices. Due to its relatively recent recognition, many regulatory boards and agencies are lacking tangible legal language concerning graywater. In most cases regarding graywater – and in particular, Colorado – legislation concerning other areas of water resource management is extrapolated to “cover” graywater. Though the benefits and lack of risk in graywater recycling are widely recognized amongst these agencies, these loose interpretations are generally used to prohibit its practice. Agencies do not prohibit graywater maliciously, but do so in precaution of legal recourse from a lack of legislation. Therefore, it is pertinent that the statutory recognition of graywater be established so that communities may reap its benefits, particularly in Colorado. In analyzing the established law in graywater and the suggested amendments to House Bill 13-1044 (the bill currently being voted on in the Colorado State Senate) were made including; a committee within Water Quality Control Division and suggested treatment standards. The inclusion would assure the inclusion of graywater recycling into Colorado’s future water conservation efforts.

Introduction

Background/Motivation

Water conservation has become one the most pressing issue in the management of natural resources. The state of Colorado finds itself in an especially important role in the management of its water resources, as it is a primary upstream provider for much of the West. The concept of conservation has been relevant for the better part of six decades; most strides in conservation have come through conservation education, BMP’s, and the increase in appliance efficiencies. According to a 2005 USGS study of water use in the United States, the amount of total water use in the United States has been relatively constant since 1980 due to these conservatory efforts, despite increases in population, food demand, industry, etc. [1] The study also demonstrated the increase in public supply withdrawal over the past 50 years, as well as a 43 percent increase in demand for irrigation purposes, both of which are a direct result of an increase in population. This trend in population growth is not only likely to remain but increase further. Conservatory action must be taken to assure an ample supply of water for the country as our population grows. One of the most immediate means to reduce the public consumption with our available technology is graywater recycling.

[1] “Trends in Water Use in the United States, 1950 to 2005.” The USGS Water Science School. 10 Jan. 2013. USGS. 20 Apr. 2013 <http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/wateruse-trends.html>.

Graywater Recycling

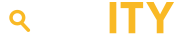

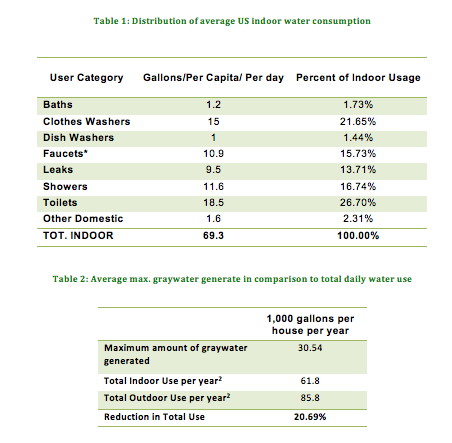

The term graywater is used to describe water that has been used in bathroom sinks, showers, tubs, and washing machines. Graywater water by treatment standards is not safe for personal consumption, however, there are many recycling methods that can be employed to get a second use out of graywater. The most common recycling methods for treated graywater are the replacement of toilet water, landscape irrigation, or a combination of both. By implementing a toilet recirculation system in the average United States household, there is a potential reduction of up to 26.7% in total indoor use as seen in Table 1.[1] Using graywater firstly to replace toilets and secondarily to replace a portion of irrigation could potentially result in a 16.37% reduction of outdoor water use. As seen in Table 2, with complete use of all graywater generated it is possible to reduce the total household consumption by 20.69% or 30,540 gallons per year. Conversely, for every gallon of white water (water before use) replaced by graywater, there is an equal reduction in the water being treated by the wastewater treatment plant. The average American family spends about $474 a year on water and sewage charges, by implementing the water reductions illustrated above, there would be a potential of approximately $98.00 in annual savings.[2] Furthermore, with a reduction in the use of any natural resource, there is also a reduction in marginal user costs not quantified, e.g. higher emergency reservoir levels for drought and fire protection (increased non-use value).

[1] Heaney, James P., William DeOreo, Peter Mayer, Paul Lander, Jeff Harpring, Laurel Stadjuhar, Courtney Beorn, and Lynn Buhlig. “Nature of Residential Water Use & Effectiveness of 45

Conservation Programs.” Boulder Community Network. Web. 12 Mar. 2012. <http://bcn.boulder.co.us/basin/local/heaney.html>.

[2] United States. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Water. Water on tap, what you need to know. 2009.

Issues and Concerns with Graywater

Though at first glance graywater seems like a no-brainer from a water conservation standpoint, there are concerns to graywater use that hold greater merit than water conservation, chiefly, public health and water rights.

Public Health Concerns in Graywater Reuse

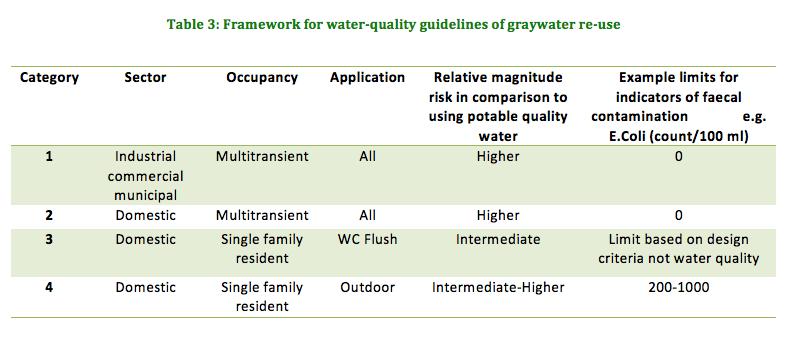

Graywater, similar to wastewater (blackwater), presents increased health risks such as microbial infection, DBP formation, and high levels of inorganic compounds. The most concerning health hazard for graywater is increased exposure to infectious microbial bacteria. Particularly precarious is Legionella pneumophila due to its resilience to water treatment processes, “It is possible that greywater-recycling equipment might provide a haven for the proliferation of the legionella bacteria”.[1] To minimize the chances of exposure, ceilings are set for the allowable quantity of microbial bacteria present in treated graywater. The primary indicator of microbial bacteria is Faecal coliform. In conjunction with the amount bacteria present, health risks can be assessed based on the end-use of the graywater (toilet flush and/ or irrigation) and number of people exposed to the treated graywater. Table 3 provides guidelines based on these risk characteristics, as present in Guidelines for Greywater Re-Use: Health Issues.[2]

[1] Dixon, A. M. Guidelines for Greywater Re-use: Health Issues. Tech. 1999

[2] Ibid

Further health concerns are generated from the self-regulation of graywater treatment systems. Unlike waste treatment plants, which are entities of local and state governments, and are held liable by regulatory boards, the owner is liable for maintaining the quality of their graywater system, which left unregulated could lead to increased public exposure.

In the state of Colorado, The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment Water Quality Control Division (WQCD) maintains drinking and wastewater treatment standards. Regulation NO. 84 – Reclaimed water control regulation, provides treatment standards specific for the treatment of wastewater, however, there is no mention on standards concerning the treatment of graywater. These standards must be established by the WQCD to ensure the safe and efficient use of graywater.

Water Rights Issues in Graywater Reuse

Historically, Colorado has always had issues pertaining to ownership of water resources. “The Colorado law governing the right to reuse or make successive use of return flows after a first use of water has been made is relatively strict compared to that in other western states”.[1] Water rights in Colorado are based on the doctrine of prior appropriation. The prior appropriation law, states “An appropriation is made when an individual physically takes water from a stream (or underground aquifer) and places that water to some type of beneficial use”. [2] The user must have court-approved water rights on the appropriated water source. Priority of said water appropriation is granted based on the first issuance of a right. Thusly, even if a water resource is over-appropriated (e.g. the volume of water available is lower than the amount distributed through water rights) the senior most holder will get their rights fulfilled before the junior rights holders, even if this means the junior gets nothing.

[1] Maynard, Alison. “The Reuse Right in Colorado Water Law: A Theory of Dominion.” Denver University Law Review 68 (1991): 413. Print.

[2] “Prior Appropriation Law.”Http://water.state.co.us/surfacewater/swrights/pages/priorapprop.aspx. Colorado Division of Water Resources. 15 Apr. 2013 <http://water.state.co.us/surfacewater/swrights/pages/priorapprop.aspx>.

The problems posed from the prior appropriation doctrine stem from the definition of use, in Colorado, “when the use has been completed the right of the user terminates”.[1] This can further imply that in order to reuse water, rights may have to be re-appropriated. Courts have historically taken the opinion that effluent flow after a use is consider a tributary to the stream, and interception of it constitutes and interference with vested water rights.[2] This legal framework was clearly established without the consideration of graywater and needs to be amended to appropriately include graywater recycling.

[1] Ibid 6

[2] Comstock v. Ramsay, 55 Colo. 144, 133 P. 1107 (1913); Ft. Morgan Reservoir &Irrigation Co. v. McCune, 71 Colo. 256, 206 P. 393 (1922). See also discussion in note 1,supra.

House Bill 13-1044

In December of 2011, House Bill 12-1003 – the initial draft for graywater use in Colorado – was introduced for consideration during the 2012 legislative session and promptly killed. House House Bill 13-1044 is the revised version of HB 12-1003, currently being reviewed by the Colorado State Senate.

HB 13-1044 is prefaced as “a bill for an act concerning the authorization of the use of graywater, and, in connection therewith, making an appropriation”.[1] The bill illustrates the importance of ensuring adequate future water supplies for economic well-being and that “the greater public interest served by policies that promote greater efficiency in the first use of water within residential, commercial, and industrial facilities”[2] The bill also legally defines graywater as: “‘Graywater means that portion of wastewater that, before being treated or combined with other wastewater, is collected from fixtures within residential, commercial, or industrial buildings or institutional facilities for the purpose of being put to beneficial uses authorized by the commission in accordance with section 25-8-205 (1) (g)”.[3] Section 25-8-205 (1) (g) provides the criteria in which the commission can set control regulations. These criteria consist of:

- “Accordance to terms and conditions for applicable decrees or well permits for source water rights source water and any return flows therefrom”[4]

- “In accordance with all federal, state, and local requirements”[5]

- “If a local government adopts a resolution or ordinance authorizing its use”[6]

Further definition is provided for the term “Graywater treatment works” as an arrangement of devices and structures used to:

- Collect graywater from within a building or facility; and [7]

- Treat, neutralize, or stabilize graywater within the same building or facility to the level necessary for its authorized uses.[8]

The bill goes on to declare municipalities and counties as the authoritative figures to authorize graywater use and enforce compliance with their regulations for its use[9]. Persons withdrawing water from a well are authorized to use graywater subject to limitations contained in their permit. Replacement plans for inclusions of graywater are also authorized if applicable[10]. For those not using well water, that are supplied by a municipality or water district’s water supply, graywater is permitted for purposes allowable under the municipality’s or water district’s water rights. Use of said graywater must be confined to the operation that generates the graywater[11], and its use is in compliance with the regulations set forth by the governing bodies[12]

Section 11 of HB 13-1044 “encourages the Examining Board of Plumbers to adopt and incorporate by reference Appendix C of the International Plumbing Code (I.P.C.), 2009 edition”.[13] Appendix C is the plumbing design code provided by the I.P.C. for the installation of graywater collection systems. Section 12 appropriates the funds needed for the payment services provided in creating the bill. The final section of the bill is a safety clause stating, “The general assembly hereby finds, determines, and declares that this act is necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, and safety”.[14]

Disregarding the legal verbiage, House Bill 13-1044 can be summarized as follows:

- The economic benefits and the greater public wellness from the use of graywater are recognized by the State of Colorado.

- The terms “Graywater” and “Graywater Works” are legally defined.

- Federal, state, and local governments maintain authoritative power over graywater use.

- Users are required to adhere to all requirements for graywater established by said authoritative powers.

- Graywater use is subject to limitation based on said users water rights, this applies to wells, municipalities, and water district rights.

- The Examining Board of Plumbers is encouraged to adopt Appendix C of the I.P.C. for local graywater plumbing code.

- The general assembly finds the act (HB 13-1044) necessary for the immediate preservation of public peace, health, and safety.

[1] Concerning the Authorization of the Use of Graywater, And, in Connection Therewith, Making an Appropriation, 1044, 69th G.A., 1 Colorado 1 (2013). Print.

[2] Concerning Graywater, Section 1 (I)

[3]Colo. Rev. Stat § 25-8-103 (8.3) (2013)

[4] Colo. Rev. Stat § 25-8-205 (2013)

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Colo. Rev. Stat § 25-8-103 (8.4) (2013)

[8] Ibid

[9] Colo. Rev. Stat § 30-11-107 (1) (kk) (2013) & Colo. Rev. Stat § 31-15-601 (1) (m) (2013)

[10] Colo. Rev. Stat § 37-90-107 (5.5) (2013), Colo. Rev. Stat § 37-90-137 (15) (2013), & Colo. Rev. Stat § 37-92-602 (1.5) (2013)

[11] Colo. Rev. Stat § 37-92-102 (7) (a) (2013)

[12] Colo. Rev. Stat § 37-92-102 (7) (c) (2013)

[13] Colo. Rev. Stat § 12-58-101 (3) (2013)

[14] Concerning Graywater, Section 13

What is missing in House Bill 13-1044

In reviewing House Bill 13-1044, I found some areas that were omitted that I believe should’ve been included. Considering Colorado’s long troubled history with water rights, it is safe to say the transition towards the inclusion graywater will not be a smooth one. To combat this I believe it is more than necessary to form a committee within the Water Quality Control Division (WQCD) to specifically handle graywater. This committee should be comprised of members knowledgeable in water rights, health and safety requirements, plumbing code, and buildings code. If this committee is not comprised and all responsibilities for graywater are placed on the current arrangement of the Water Quality Control Division (as is implied by the bill), the chances of there being an “immediate” impact are slim considering the bureaucratic natural of water rights.

Though each state and county’s water treatment standards vary, it would be beneficial to include a recommendation of adoption or consideration for an established set of treatment criteria. Graywater has been around in the western US for the better part of two decades and there are several states with similar climates (e.g. Wyoming) that could be preferentially used as guidelines for establishing health standards. Similar to the recommendation of the general assembly to the Examining Board of Plumbers to adopt the I.P.C., the General Assembly could recommend that the WQCD adopt the World Health Organization’s Volume 4, Excreta, and Graywater Use in Agriculture as a reference for health and safety requirements.

Though these recommendations won’t be included in this version of the bill on the floor currently, HB 13-1044 still presents a very good first step for the progress of graywater. With a promising political atmosphere in favor of water conservation efforts – unlike the atmosphere present during the initial draft of the bill (HB 12-1003)[1] – HB 13-1044 stands a very good chance of passing the Senate. If the bill does pass, however, there are still several things that still need to occur before graywater will be available for installation to the residents and industries of Colorado.

[1] Hickenlooper, John. “Coyote Gulch.” Interview by Dallas Heltzell. Coyote Gulch. 25 Apr. 2013 <http://coyotegulch.wordpress.com/2013/05/03/2013-colorado-legislation-graywater-bill-may-make-it-to-governor-hickenloopers-desk-this-session/>.

The Next Steps

On the likelihood that HB 13-1044 passes there are roughly four more stages until graywater can be fully proliferated. The first process to take place will be the promulgation of rules and standards for graywater currently not in place. This will take place in the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, specifically the Water Quality Control Department. The Department will have several decisions to make in terms of the regulations they want to provide. The main decision to be made is whether systems are going to be regulated by design requirements (e.g. The overflow system must be designed so that the tank overflow will gravity drain to the existing sewer line or septic tank.[1]) or based on the achievement of treatment goals (e.g. TSS less than 30 mg/L (30-day average) and 45 mg/L (seven-day average)[2]). Arizona has a particularly encouraging system based on achievement of treatment goals. Goals are established based on tiers of flow, ranging from <400 gpd (tier 1), between 400-3000 gpd (tier 2), and >3000 gpd (tier 3). This structure is particularly efficient because it provides explicit designs as options, but does not require specific systems. By having looser system requirements it is easier for those eager to use graywater to design a system within their means.

Once the rules and minimum statewide standards are established for treatment systems, the Colorado Examining Board of Plumbers must develop a plumbing code for graywater that provides installation guidance for installers.[3] Judging by the language in HB 13-1044 this will be some variation of Appendix C from the I.P.C.

After the plumbing board establishes a statewide standard for installers, the process moves forward to the local Colorado governments for further regulations. Local boards will adopt ordinances in consultation with local health boards and water and wastewater service providers.[4] Though all the governing bodies and laws will be in place it is likely graywater won’t click immediately.

Similar, to recycling in the 70’s and 80’s, graywater will take sometime to become a normal practice. However, with education and outreach this process can be accelerated. This ranges from educating citizens about the potential benefits and dispelling rumors to create demand, to providing the knowledge and skills to laborers so that there is a supply of systems. In the coming years as the climate changes and water shortages occur more frequently, water conservation will become particularly relevant and graywater will hopefully follow suit.

[1] Cali. Code of Reg., Title 24, Part 5, Chapter 16A, Part 1 §1609A.0 Tank Construction

[2] Arizona Title 18, Chapter 9, §R18-9-B204 Treatment Performance Requirements For New Facilities

[3] Ibid 24

[4] Ibid 24

Conclusion

With Colorado being the “only arid western state whose statutes [do not] recognize or explicitly authorize the installation or operation of gray-water systems”[1] and our water demands increasing every day it is very likely HB 13-1044 will be approved in the near-future. Pilot programs such as those being initiated at the Williams Village North dormitories at the University of Colorado Boulder are providing valuable insight into the viability and performance of graywater recycling. These programs will help provide baseline data to help further the use of graywater in a broader range of users. Though the immediate economic benefits of graywater are limited, pilot programs can showcase the water conservation efficiencies that will certainly be needed in our near future, when the economic value will be much greater. Furthermore, pilot programs will provide education to a multitude of citizen unaware of graywater. At the moment we can only hope that Colorado politicians are as serious about water conservation as they profess they are. There’s a long way to go until graywater recycling is a common everyday practice, but as of today were are heading in the right direction.

[1] Ibid 24

References

Arizona Title 18, Chapter 9, §R18-9-B204 Treatment Performance Requirements For New Facilities

Cali. Code of Reg., Title 24, Part 5, Chapter 16A, Part 1 §1609A.0 Tank Construction

Comstock v. Ramsay, 55 Colo. 144, 133 P. 1107 (1913); Ft. Morgan Reservoir &Irrigation Co. v. McCune, 71 Colo. 256, 206 P. 393 (1922). See also discussion in note 1,supra.

Concerning the authorization of the use of graywater, and, in connection therewith, making an appropriation, 1044, 69th Cong., 1 Colorado 1 (2013).

Dixon, A. M. Guidelines for Greywater Re-use: Health Issues. Tech. 1999.

Heaney, James P., William DeOreo, Peter Mayer, Paul Lander, Jeff Harpring, Laurel Stadjuhar, Courtney Beorn, and Lynn Buhlig. “Nature of Residential Water Use & Effectiveness of 45

Conservation Programs.” Boulder Community Network. Web. 12 Mar. 2012. <http://bcn.boulder.co.us/basin/local/heaney.html>.

Hickenlooper, John. “Coyote Gulch.” Interview by Dallas Heltzell. Coyote Gulch. 25 Apr. 2013 <http://coyotegulch.wordpress.com/2013/05/03/2013-colorado-legislation-graywater-bill-may-make-it-to-governor-hickenloopers-desk-this-session/>.

Maynard, Alison. “The Reuse Right in Colorado Water Law: A Theory of Dominion.” Denver University Law Review 68 (1991): 413. Print.

“Prior Appropriation Law.” Http://water.state.co.us/surfacewater/swrights/pages/priorapprop.aspx. Colorado Division of Water Resources. 15 Apr. 2013 <http://water.state.co.us/surfacewater/swrights/pages/priorapprop.aspx>.

“Trends in Water Use in the United States, 1950 to 2005.” The USGS Water Science School. 10 Jan. 2013. USGS. 20 Apr. 2013 <http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/wateruse-trends.html>.

United States. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Water. Water on tap, what you need to know. 2009.